Given that the stock market, as a leading economic indicator, anticipates economic turning points, the sharp decline and volatility over the last weeks of several stock indices globally, clearly indicates that the Covid-19 crisis will have a significant economic impact. It is, therefore, not unthinkable that (groups of) companies will find themselves facing pertinent liquidity issues that might even evolve into solvability issues.

Governments and international institutions are taking hard measures to assist solvable companies in remaining in business (“wielding bazookas”) to soften the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, parent companies or entities managing the treasury function will consider their options to provide liquidity carefully. This article will go into more detail in liquidity management through debt and equity. Of course, also other measures could be considered such as providing extensions of payment terms, cash pools (although it should be carefully monitored whether maintaining certain levels of debit or credit positions as short-term liquidity, that could become rather more long term positions especially considering tax authorities often attempt to requalify such positions to longer term deposits or term loans), etc.

Providing the necessary liquidity via debt instruments (e.g. intercompany loans) could of course be an option. Please note that in this respect, the OECD recently published additional guidance on financial transactions and some local tax authorities1 implemented their interpretation of this guidance into local law or guidance.

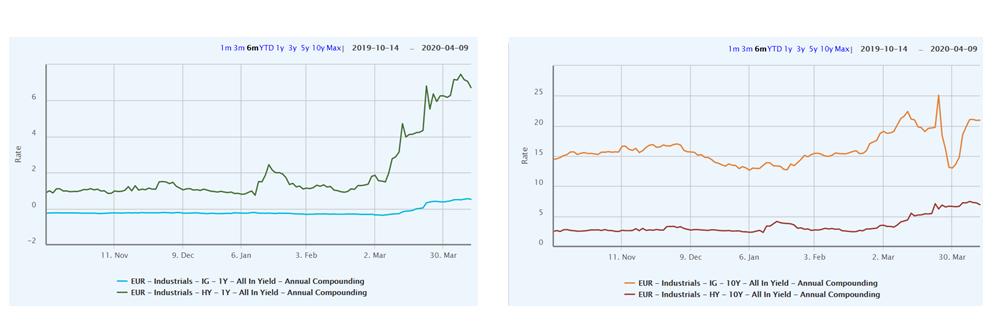

Moreover, due to the turmoil on the markets, the arm’s length interest rates are on the rise. Although the impact on investment grade rated debt instruments could be viewed as limited considering interest rates for both short term as long term “only” rose with about 0.8% (a relative increase of around 290% and 80% respectively), the impact on non-investment grade rated debt instruments is much more significant. On average, high-yield short term interest rates increased with 5.8% (a relative increase of around 630%!), longer term interest rates increased with 4.35% (a relative increase of around 170%). These rates are based on the following S&P Capital IQ EUR Industrial yield curves (for corporate bonds).

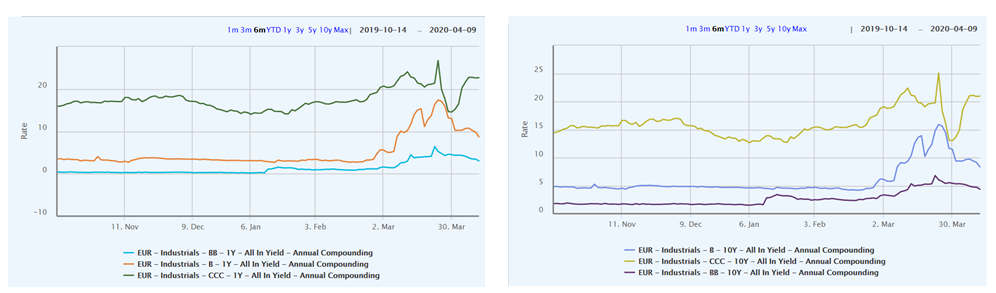

The above increases are the average of the non-investment grade credit ratings. Given the interest rates even under normal market conditions, exponentially increase when moving towards a creditworthiness of CCC, the interest rates linked with a credit rating of B or CCC rose much higher compared to the average of non-investment grade (e.g. In the (B) rating class a whopping +8.4% can be observed by the end of March, which decreased to still a significant +5.6%). Additionally, as can be seen on the stock market as well, volatility is going through the roof. This is not only shown clearly on the charts below by the (B) and the (CCC) rating classes but which is also shown by an increase of the VIX index2 (peaking at more than 400% compared to end of 2019 levels around half March, and today still about 200% more compared to end of 2019 levels).

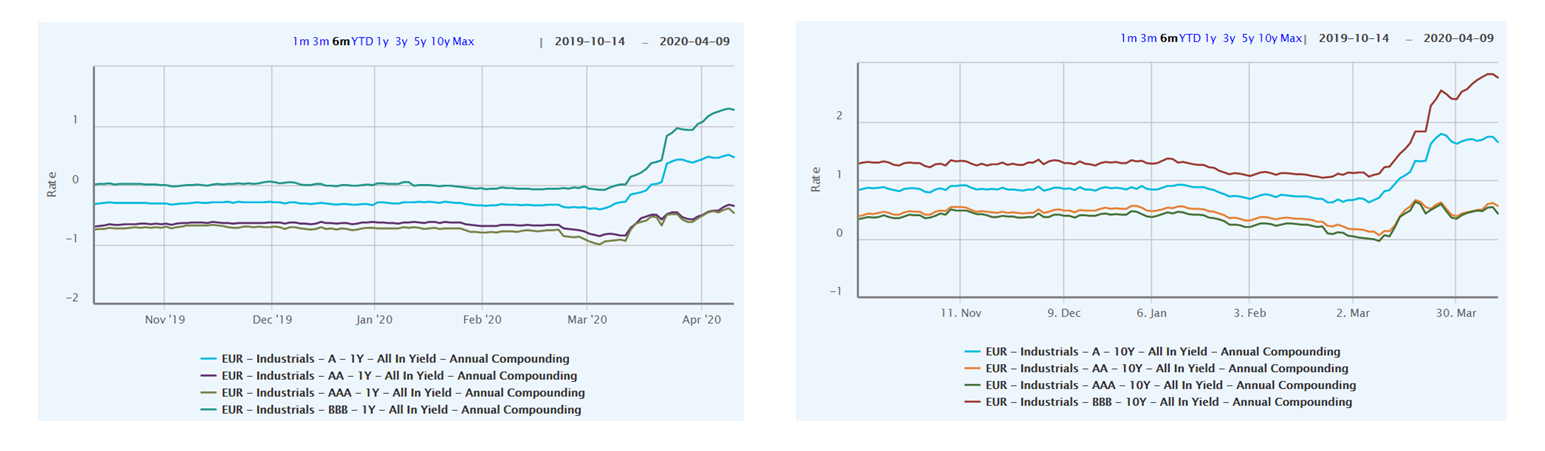

If we take a more detailed look at those short-term rates, we see that as from the beginning of March the (A) rating class becomes positive for the first time since over 4 years which is a relative increase of about 230%. The increase of the (BBB) rating class, however is more significant, increasing from around 0% at the beginning of the year to around 1.30%. the (AA) and (AAA) investment grade classes still are below 0 and increased relatively limited with around 0.25% (relative increase of 44% and 35% respectively). With respect to non-investment grade rating classes, there is obviously more volatility. The chart clearly shows the significant rise of the (B) rating class. Although interest rates decreased slightly from its peak at the end of March, interest rates with respect to the (B) rating class are still up with 5.6% compared to interest rate levels at the end of 2019. Moreover, while the absolute increase of interest rates in the (BB) rating class are about half of those in the (B) rating class, a relative increase of 1110%(!) can still be observed.

With respect to the long-term interest rates using a tenor of 10 years, we see the same overall pattern. Interest rates for both investment grade rating classes and non-investment grade rating classes are less impacted. Indeed, regarding investment grade classes, interest rates for the (AA) rating class did not see an impact (relative increase of 0%), while for the (AAA) rating class interest rate went down compared to end of 2019 levels. (A) and (BBB) rating classes increased with about 0.8% and 1.4% respectively which corresponds to a relative increase of around 100%. Regarding non-investment grade classes, please note that as from the (B) rating class3, the yield curve is still inverted, i.e. the short-term interest rate is higher than the longer-term interest rates.

Disregarding the inversion of the yield curves as from (B) rating classes, for companies in financial distress, looking for liquidity to overcome the current Covid-19 pandemic, it would make sense to borrow short-term. Not only the interest rate would be lower, financial distress would, hopefully, disappear as soon as the economy revamps which, again hopefully, will happen in the short term rather than the long term.

Additionally, although special market conditions could explain special measures, debt/equity levels should be considered as well. Indeed, although liquidity needs might only exist for the short term and, therefore, only the short term debt/equity level might deviate from what is expected to be normal, tax authorities might still argue that such debt/equity level are not in line and, hence, reject (part of) the funding provided as debt and requalify as equity, leading to disallowed interest deductions.

Given that debt funding might not be an optimal solution under the given circumstances (or it could be no option at all if companies under financial distress suffer losses possibly resulting in negative equity values), one could consider other options.

A debt waiver for instance, was a popular tool during the last financial crisis. Since the last crisis however, due to changes in the income tax codes, a debt waiver might produce a minimum tax to be paid, and hence a cash out which is to be avoided. A debt waiver would typically result in taxable income at the level of the borrower. Given the (carried forward) losses that might arise at this level, this taxable income can be sheltered. However, since the last crisis, due to changes in the income tax codes, a debt waiver might produce a minimum tax to be paid as carried forward tax losses are allowed for only a partial compensation. Furthermore, if no debt waiver clause is agreed upfront and included in the loan agreement, options realistically available (“ORA”) for both lender and borrower should be considered. It is also advisable to review specific force majeure clauses (where relevant), although comparability with third party behavior and ORAs remain most relevant. Taking into account the current market conditions, in most cases the fair value of the debt instrument would have a latent loss which should be considered as well. Additionally, when agreeing on a debt waiver, one might consider a clause in case the group affiliate returns to realize profits so that the loan is reinstated. This would de facto be similar to providing an extension of payment terms, however for an undefined period and potentially linked with certain profitability thresholds which are to be reached before such loans are automatically reinstated. In any case, when reinstating a loan after a debt waiver, again, ORAs of both lender and borrower should be considered.

In case waiving debt is not considered to be a good option to tackle financial distress, companies could also make a contribution in kind of intercompany debt instruments. In case when such debt-equity swaps are considered, it is important to focus on the exchange ratio, i.e. the amount of shares issued with respect to the contribution. Indeed, as mentioned above, the fair value of the intercompany debt instrument probably has a latent loss. Furthermore, the fair value of the shares is another important factor to consider. When the transaction would be under scrutiny from the tax authorities, it cannot be excluded that they will attempt to use hindsight to determine fair value. Therefore, it is recommendable to have sufficient support in the determination of the fair value of the debt instrument as well as the fair value of the shares.

Although no one size fits all solution is readily available, a customized option for a companies’ specific circumstances and needs can be found. However, although the goal is to provide liquidity in times when affiliates really need it, tax authorities might come back in future years to bite if the chosen option is not supported sufficiently. Let’s hope the Covid-19 pandemic will disappear swiftly, and above measures are not necessary. In case measures are necessary, do not consider lightly the impact such measures can have on future (tax) years.

Andy Neuteleers - Partner (Andy@TAeconomics.com)

Kenny Van Tulder - Sr. Manager (Kenny@TAeconomics.com)

Ben Plessers – Sr. Manager (Ben@TAeconomics.com)

1 For instance, the Belgian tax authorities published a Circular Letter on Transfer Pricing (we refer to http://www.taeconomics.com/newsflash-belgian-tax-administration-releases-circular-letter-transfer-pricing)

2 The VIX Index is a calculation designed to produce a measure of constant, 30-day expected volatility of the U.S. stock market, derived from real-time, mid-quote prices of S&P 500® Index (SPXSM) call and put options. On a global basis, it is one of the most recognized measures of volatility -- widely reported by financial media and closely followed by a variety of market participants as a daily market indicator.

3 Please note that regarding the (BB) rating class, the yield curve is still inverted in the very long term. The S&P EUR industrials BB 30-year interest rate is lower than the 20-year.